More about the English Lakes

More about the English Lakes |

In October 1957

Britain spread a plume of radioactive contamination into the atmosphere from

a nuclear reactor fire at Sellafield. Documentary on how UK developed its atomic bombs...

Having helped the US Manhattan Project develop the atom bomb at the end of the

Second World War, the British government felt it had to develop its own A bomb

to be able to stay “at the Top Table” as a world power. The Americans

had refused to allow Britain to have the weapons technology its own scientists

had helped develop.

Without any reference

to Parliament great energy was poured into producing a British bomb. (The first

time MP s were told officially was through a brief announcement in 1947) One key requirement were reactors to burn uranium and produce plutonium. It

was decided to use an old ammunition factory at Windscale (now called Sellafield).

The site had plenty of cooling water from Wastwater lake and was remote from

population in case of any accidental nuclear incidents. At a time of post war

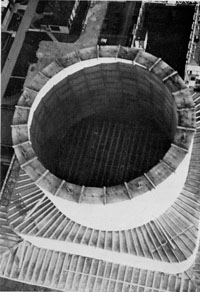

austerity two huge heavily shielded reinforced concrete “piles” were

built at break neck speed and by 1950 the piles were operating. Alongside the

first nuclear reprocessing plant (B204) had also been built to extract the precious

plutonium.

One key requirement were reactors to burn uranium and produce plutonium. It

was decided to use an old ammunition factory at Windscale (now called Sellafield).

The site had plenty of cooling water from Wastwater lake and was remote from

population in case of any accidental nuclear incidents. At a time of post war

austerity two huge heavily shielded reinforced concrete “piles” were

built at break neck speed and by 1950 the piles were operating. Alongside the

first nuclear reprocessing plant (B204) had also been built to extract the precious

plutonium.

It was in February 1952 that the first salmon tin sized billets of plutonium were ferried south in the boot of a taxi to the new Aldermaston weapons factory near Oxford. Britain’s first A bomb, code named Hurricane was detonated off the cost of Australia in October 1952. These early plutonium reactors were crude affairs with the main objective being to get the weapons material as quickly as possible. Each “pile” was a honeycomb of carved graphite blocks. Hundreds of horizontal channels ran from the front (charge face) of the reactor to the rear discharge face. Some 35,000 aluminium cans of uranium were pushed into these channels to assemble the critical mass for the chain reactions to burn away.

As

they generated the intense heat and neutron flux of a nuclear chain reaction

some of the uranium converts into plutonium. The fuel cans which had undergone

this fiery transformation were a few weeks later pushed through to drop out

of the discharge side of the reactor. They then travelled by a mini boat along

a water duct into the adjoining reprocessing plant. All this had to take place

behind several feet of concrete shielding to cut down the intense penetrating

radiation. Each reactor weighed a total of 57,000 tonnes. Because the graphite

could release its own latent heat suddenly and unexpectedly the entire reactor

had to be deliberately heated up to aneal the graphite.

As

they generated the intense heat and neutron flux of a nuclear chain reaction

some of the uranium converts into plutonium. The fuel cans which had undergone

this fiery transformation were a few weeks later pushed through to drop out

of the discharge side of the reactor. They then travelled by a mini boat along

a water duct into the adjoining reprocessing plant. All this had to take place

behind several feet of concrete shielding to cut down the intense penetrating

radiation. Each reactor weighed a total of 57,000 tonnes. Because the graphite

could release its own latent heat suddenly and unexpectedly the entire reactor

had to be deliberately heated up to aneal the graphite.

On October

8, 1957 a technician was heating up the reactor to release this so called Wigner

energy. Because of the inadequacy of the temperature measuring instrumentation

the control room staff mistakenly thought the reactor was cooling down too much

and needed an extra boost of heating. Thus temperatures were actually abnormally

high when at 11.05am the control rods were withdrawn for a routine start to

the reactor's chain reaction. A canister of lithium and magnesium, also in the

reactor to create tritium for a British H bomb, was probably the first can to

burst and ignite in the soaring temperatures. This coupled with igniting uranium

and graphite sent temperatures soaring to 1,300 degrees centigrade.

On October

8, 1957 a technician was heating up the reactor to release this so called Wigner

energy. Because of the inadequacy of the temperature measuring instrumentation

the control room staff mistakenly thought the reactor was cooling down too much

and needed an extra boost of heating. Thus temperatures were actually abnormally

high when at 11.05am the control rods were withdrawn for a routine start to

the reactor's chain reaction. A canister of lithium and magnesium, also in the

reactor to create tritium for a British H bomb, was probably the first can to

burst and ignite in the soaring temperatures. This coupled with igniting uranium

and graphite sent temperatures soaring to 1,300 degrees centigrade.

These early plutonium "piles" were cooled by massive fans blowing air through them. The heat and some contamination was then carried up the famous concrete chimneys that are such a symbol of the Sellafield skyline. As the fire raged radioactivity was carried aloft. Blue flames shot out of the back face of the reactor and the filters on the top of the chimneys could only hold back a small proportion of the radioactivity. An estimated 20,000 curies of radioactive iodine escaped along with other isotopes such as plutonium, caesium and the highly toxic polonium.

In the days that followed a dangerous cloud of 'fallout' was carried in a south easterly direction towards cities in the North of England. The scientists were unsure how to deal with the raging fire. Workers were sent in relays to use scaffolding poles to frantically push out hundreds of fuel cans to try and make a fire break around the fire. Then they tried to pump in carbon dioxide gas to try and smother the flames, but the heat was such that oxygen was produced from the gas and thus fed the flames higher. The scientists then had to gamble on flooding the reactor with cooling water. The risk they were aware of was that explosive hydrogen and or acetylene gas could be created and then flash over into an explosion. As this critical decision was being taken the temperatures were climbing by 20 degrees a minute.

Luckily the gamble paid off and the water starved the fire of oxygen and the reactor was brought under control. Yet even today as the fateful chimneys are slowly taken down by shielded robots the centre of the fire crippled reactor of Pile one still contains molten uranium and still gives off a gentle heat. There is still unreleased Wigner energy in the graphite and water hoses are still left connected to the charge face as a final safety precaution.

Despite reassurances given to the public at the time the official National

Radiological Protection Board estimated in a 1987 study that at least 33 people

are likely to die prematurly from cancers as a result of the accident.

(Pictured are the concrete pile chimneys and radiation workers at work at Sellafield

some time after the fire incident.)

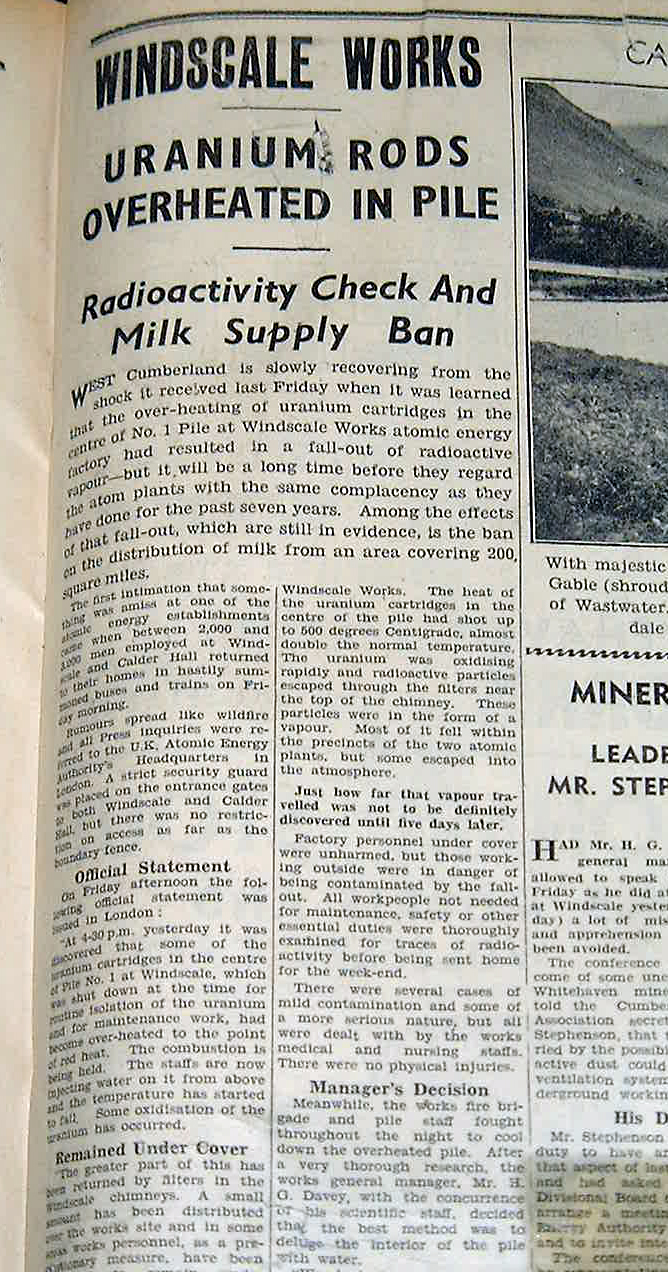

How the local press reported the incident:

Whitehaven News Thursday October 11.

Uranium Rods Overheated in Pile.

West Cumberland is slowly recovering from the shock it received last Friday

when it learned that the over-heating of uraniumcatridges in the centre of No1

Pile at Windscale Works atomic energy factory had resulted in a fall out of

radioactivite vapour-but it will be a long time before they regard the atom

plants with the same compulsory as they have done for the past seven years.

Among the effects of that fall-out, which was still in evidence, is the ban

on the distribution of milk from an area covering 200 square miles.

The first intimations that something was amiss at one of the atomic energy establishments

came when between 2,000 and 3,000 men employed at Windscale and Calder Hall

returned to their homes in hastily summoned buses and trains on Friday morning.

Rumours spread like wildfire and all Press inquiries were referred to the UK

Atomic Energy Authority's headquarters in London. A strict securityguard was

on the entrance gates to both Windscale and Calder Hall, but there were no restictions

as far as the boundary fence.

On Friday afternoon (Oct 11) the following official statement was issued in

London:

"At 4.30pm yesterday it was discovered that some of the uranium cartidges

in the centre of Pile 1 at Windscale, which was shut down at the time,for routine

isolation of the uranium and for maintenance work, had become over-heated to

the point of red heat. The combustion is being held. The staffs are now injecting

water on it from above and the temperature has started to fall. Some oxidation

of the uranium has occured.

"The greater part of this has been returned by filters in the Windscale

chimneys. A small amount has been distributed over the works site and in some

areas works personnel, as a precautionary measure, have been instructed to stay

under cover.

"Health physics personnel are carrying out a check on both the site and

in the surrounding district to ensure that any increase in the amount of radiaoactivity

may be known. There is no evidence of there being any hazard to the public."

"The type of accident that has occurred could only occur in an air-cooled,

open circuit pile and could not occur at Calder Hall or any of the power stations

now under construction by the Electricty Authority.

"At this stage it is not possible to give the cause of the accident. It

is likely the Pile will be out of operation for some months. Further reports

will be issued."

As the news flashed around the world a spate of inquiries flooded into local

newspapers and national reporters swooped.

Gradually the picture emergedof what was happening inside Windscale works. the

heat of the uranium cartridges in the centre of the pile had shot up to 500

degreesCentrigarde, almost double the normal temperature.

The uranium was oxidising rapidly and radioactive particles escaped through

the filters near the top of the chimney. These particles were in the form of

a vapour. Most of it fell within the precincts of the two atomic plants, but

some escaped into the atmosphere.

Just how far that vapour had travelled was not to be definetely discovered until

five days later. Factory personnel under cover were unharmed, but those outside

were in danger of being contaminated by the fall-out. All staff not needed for

maintenance, safety or other essential duties were thoroughly examined for traces

of radioactivity before being sent home for the weekend.

There were several cases of mild contamination and some of a more serious nature,

but all were dealt with by the works medical andd nursing staff. There were

no physical injuries.

Meanwhile the work's fire brigade and pile staff fought throughout the night

to cool down the overheated pile. After a very thorough research the works general

manager Mr H G Davey, witht the concurrence of his scientific staff, decided

the best method was to deluge the interior with water.

"We had to ensure a real torrent of water" Mr Davey told a News reporter."Too

little water could have resulted in the release of hydroge, so we pumped water

in at the rate of 1,000 gallons a minute and kept on pumping it."

This treatment went on continuously for three days and gradually the temperature

inside the pile began to fall. By Sunday night the pile had cooled off to such

an extent that only a small volume of water was necessary to keep it at a safe

level."

The number two pile was temporarily shut down so that experienced personnel

could join in the operation but it was restarted later and gradually worked

up to normal. The pile in which the mishap occured will be out of commission

for several months."

Radioactive Milk headline

Then came disturbing reports from the monitoring vans which were touring the

district testing vegetation and air. For an area of some 14 square miles around

Windscale the health staff had detected an increase in the radioactivity of

grass.It was realised that radioactive iodine would be passing into the digestive

system of cows and contaminating their milk. On Saturday night a ban was placed

on the use of milk from all dairy heards in a 14 square mile area. At the request

of Mr Davey police and Milk Marketting Board officials toured the area from

midnight onwards. Farmers were got out of their beds to be told not to dispose

of their milk in any way. They were not to feed it to stock,drunk by their own

families or sold off the farms.

West Cumberland

News of October 12 price two pence...

"No Public Danger" announcement.

Rumours of a fire in one of the piles at Windscale works atomic energy factory

swept though west cumberland yesterday morning and they gained in strngth when

hundreds of men not employed on maintenance and safety work returned to their

homes by bus and train.

A strict security guard was thrown round the two sites and officials refused

to answer telephone inquries from the press. then at 1 pm the following notice

was issued from London to BBC and ITV....A

News reporter who toured the district found no signs of panic. Some people living

within a mile of Sellafield were not even aware of anything untoward.

"Outwardly there were no signs at Sellafield that things were other than

normal." he reported. "There were few people to be seen walking about

and a security guard was mounted at the entraces to the works.

"Two hundred yards from the pile I saw septuagenerian Mrs Stanley, whos

family had been Lords of the Manor for over 600 years, calmly planting out wallflowers

in the garden in front of her cottage. I asked if she was at all worried by

what was happening at the atomic factory. She replied; "No, why should

I be? If there was anything to worry about they would have told me by now. In

any case my family have been here for over 600 years and I am staying here."

"Just across the road I saw farmer John Bateman, he told be he was not

worried and in fact did not know much about what had happened. "Down at

the villaqge school I asked headmaster Joseph Tracey if any arrangements had

been made for evacuating the children if there was any increase in radioactivity

in the district. He said all he knew about it was what he had heard on the radio

and no evacuation had been considered."

More

about Sellafield

Web site of UK government's radiation CEFAS surveys

|

Left: How the Fire was reported in the local press Documentary on how UK developed its atomic bombs... Lakestay home page

|