|

Child Labour / Collieries

of Whitehaven /England's

first Undersea mine/Haig

Mine Museum /Klondike in Cleator Moor /

/ Whitehaven's mining professor/

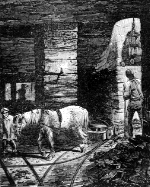

Whitehaven grew from a sleepy fishing village to a busy industrial port largely because the nearby hills had rich coal seams that were so close to the surface they even outcropped on the valley side. Such was the demand for labour that children were much employed down these early collieries. One such was Sarah (Sal) Madge.

At

the age of eight she began work at the mines. This was before

the 1842 Act of Parliament preventing women and girls from working

beneath the ground. Sal understandably hated this work dirty and

dangerous work. She only spent a brief period at this work at

Saltom pit the first ever under-sea colliery in the world. Its

twin stone lined shafts are now classed as a world heritage site,

yet are a sad derelict site on the beach. At Saltom the coal was

first raised to the beach level and then hauled up a second shaft

to Raven Hill on the cliffs above.

At

the age of eight she began work at the mines. This was before

the 1842 Act of Parliament preventing women and girls from working

beneath the ground. Sal understandably hated this work dirty and

dangerous work. She only spent a brief period at this work at

Saltom pit the first ever under-sea colliery in the world. Its

twin stone lined shafts are now classed as a world heritage site,

yet are a sad derelict site on the beach. At Saltom the coal was

first raised to the beach level and then hauled up a second shaft

to Raven Hill on the cliffs above.

From here the coal wagons carrying huge baskets of coal travelled by gravity

down to Hurries on the harbourside. Here the coal wagons were upended into the

holds of waiting sailing coal brigs. Sal worked for most of her life with the

tough horses used to move these waggons of coal to the harbourside.

She worked as a horse driver at Wilson, Croft, Ravenhill and Wellington pits.

Although of small stature Sal had become very strong through having to control

and master the colliery horses. Sal Madge, who was born in 1831, worked in the

town's colliery, drank pints, kept her hair short, smoked a pipe and wrestled

men for sport.

She wore her hair cropped short, with a man's parting and a cloth cap. Her only

concession to femininity was to wear a skirt, but for the rest she wore a shirt

waistcoat and jacket. Chewing tobacco no doubt added to her 'charm.' Local coal

magnate, Earl Lonsdale even mistook Sal for a man when he met her one day.

But like Barny the Goose, which used to live on the harbourside, Sal became

something of a myth after her death in 1899. At her death the Cumberland Pacquet,

one of the town's many newspapers, described her as "one of the last remaining

worthies of the town.''

Their report stated; "The funeral was very largely attended.... It was

a simple little funeral, and on the coffin lay just one cross of daffodils,

a touching tribute by some friend of this strange woman.''

Howgill Area (1675-1735) Radcliff Bank Pit, Causey Head Pit, Burnt Pit, Swinburn

Pit, Crayson Pit, Bell Pit, Skelton Bank Pit, Howgill Head Pit, Pickeron Bank

Pit, Senhouse Pit, Gill Close Pit, Gibson Pit, Murray Pit, Mallison Pit, Pow

Pit, Andrew Pit, Forbes Pit, Granger Pit, Darby Pit, Gameriggs Pit 1685 , Coalgrove

Pit, Wreah Pit 1820 , Scott Pit. He then lists other pits with approximate dates:

Haig Pit 1907, William Pit 1857, Henrey Pit 1837, Croft Pit (Woodhouse) 1774,

Ladysmith Pit 1898, George Pit (Top of Victoria Road)1755, Parker Pit 1738,

Lady Pit (Sunny Hill) 1728, Harris Pit (Harras Moor) 1730, Davey Pit (Hope Hall)

1735, Countess Pit (Seven Acres Parton)1780, Jackson Pit 1730, Wolf Pit 1720,

Taylor Pit 1745, Daniel Pit 1760, Bateman Pit 1710, Partis Pit (Stanley Pond)1790,

Hope Pit 1740, Howe Pit 1695, White Pit 1710, Tate Pit 1728, John Pit (Lowca)

1838. Jane Pit 1829,  Moss Pit (Sandwith road) 1780,

Dyan Pit 1730, Venture Pit 1740, Castle Rigg Pit 1785, Bottom Bank Pit, Thwaite

Pit 1755, Saltom Pit (Beach below Kells)1728, Walkmill Pit Moresby Parks)1876,

Whinney Hill Pit(Mill Hill) 1848, Fox Pit 1755, Duke Pit (Rosemary Lonning)

1745, Kells Pit (North of Haig)1750, Corporal Pit (Preston Street) 1737, Greenbank

Pit (next cemetery) 1675, Knockmurton Pit (near cemetery) 1670, Woodgreen Pit

1679, Ravenhill Pit(Kells) 1736, Lattera Pit (Moresby Parks) 1695, Priestgill

Pit (Hensingham) 1688, Ginn Pit 1700, Stone Pit 1705, Fish Pit 1765, Wilson

Pit (Sandwith road) 1740, King Pit 1725, Arrowthwaite Pit 1715, Newtown Pit

(Preston St) 1700, Hind Pit 1700, Country Moor Pit 1710, Carr Pit 1720, Pearson

Pit 1730, Pedlar Pit 1710, Taylor Pit 1700, Fox Pit 1700, Daniel Pit 1710, Jackson

Pit 1705, Hunter Pit 1695, Watson Pit 1705, Green Pit 1700, Lady Pit (Sunny

Hill)1728.

Moss Pit (Sandwith road) 1780,

Dyan Pit 1730, Venture Pit 1740, Castle Rigg Pit 1785, Bottom Bank Pit, Thwaite

Pit 1755, Saltom Pit (Beach below Kells)1728, Walkmill Pit Moresby Parks)1876,

Whinney Hill Pit(Mill Hill) 1848, Fox Pit 1755, Duke Pit (Rosemary Lonning)

1745, Kells Pit (North of Haig)1750, Corporal Pit (Preston Street) 1737, Greenbank

Pit (next cemetery) 1675, Knockmurton Pit (near cemetery) 1670, Woodgreen Pit

1679, Ravenhill Pit(Kells) 1736, Lattera Pit (Moresby Parks) 1695, Priestgill

Pit (Hensingham) 1688, Ginn Pit 1700, Stone Pit 1705, Fish Pit 1765, Wilson

Pit (Sandwith road) 1740, King Pit 1725, Arrowthwaite Pit 1715, Newtown Pit

(Preston St) 1700, Hind Pit 1700, Country Moor Pit 1710, Carr Pit 1720, Pearson

Pit 1730, Pedlar Pit 1710, Taylor Pit 1700, Fox Pit 1700, Daniel Pit 1710, Jackson

Pit 1705, Hunter Pit 1695, Watson Pit 1705, Green Pit 1700, Lady Pit (Sunny

Hill)1728.

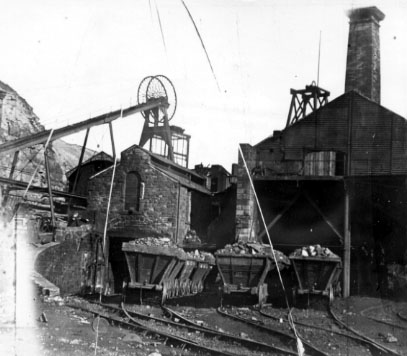

May 2000 marks the 90th anniversary of the worst disaster in the Cumbrian coalfield,

the day 136 men and boys died in the 1910 explosion at Wellington Pit.

Whole families were wiped out, funerals went on for weeks. Wellington Pit closed

in 1932.

Saltom Pit pithead (pictured left)complex below the cliffs at Kells,

Whitehaven is a World Heritage Site. As the

mine was aimed at risking the speculators' capital in winning coal from beneath

the sea it was located just 20 feet above sea

level on a bay beneath the cliff. And therein lies the big problem over the

future preservation of this historic site. The shaft was hourgl;ass shaped with

timber balks between, half being for updropughgt of foul air and the other for

the indrought of fresh air.

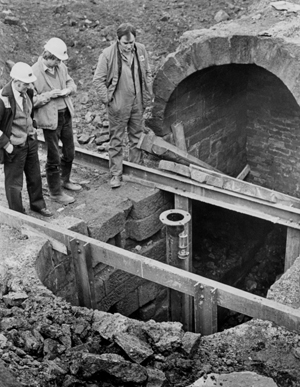

On

one side the sea is trying to erode the shore, while from the other side the

cliff side is crumbling and invading the area. One of

those who has long campaigned for the site to be preserved and used as a historic

feature for visitors and locals alike is county councillor Ron Calvin. A former

miner himself, county councillor Ronnie Calvin, explains: "The mine was

sunk in 1729 and was possibly the first and biggest undersea coal mine in the

world. It was worked until 1847 when it stopped drawing coal.''

Coun Calvin says he has repeatedly pressed for more action and even mentioned

the sad state of the Saltom Pit remains when he met John Prescott, on his visit

to officially open Whitehaven's lockgates. The mine shaft was dug as an unusual

oval in shape, to the depth of 76 fathoms. The hour-glass shaped design meant

timber balks were slotted down the centre to split the shaft into an up and

down sections for ventilation. When the men were digging and stone lining this

shaft they broke into a

powerful blower of the explosive methane gas that has turned so many Whitehaven

mines into fire traps. On this occasion the

engineer, Carlisle Spedding, showed talent in piping the gas to the surface

where it was used to illuminate the pit head

complex. He even offered the gas for free to the town, but perhaps short sightedly,

the Town Trustees turned down this

chance to light the town for free! Carlisle Spedding had a massive Newcomen

steam pumping engine, built at the sea shore pit head, to enable the constant

inflow of water to be pumped out. The mine was worked until 1848. Among the

ruins are traces of the circular Gin area in which horses patiently plodded

their way round and round to haul up the tubs of coal from the bottom of the

shafts. The site is owned by Copeland Council, who have to grapple with the

difficult issue of how to fund its preservation. They have approached the government

for assistance with funding but were turned down. Chris Lloyd,

Copeland's Head of Contracts & Projects Management, said: "Copeland

Borough Council does recognise the historic

importance of the pit remains and members have considered the options available

for their protection. Unfortunately these

remains are located in a difficult position, being relatively close to the beach

and on a small plateau only slightly above beach

level. "The sea defence gabions have been partially breached by the extreme

tidal conditions in recent years and there have

been some movement of the cliff adjacent to the gabions. "To compound the

problem the South Shore cliff extends

immediately behind the remains. This cliff is substantially overtopped with

tipped former mine workings and over a period of

time these have started to settle. Tension cracks have appeared in a number

of places above and to the north of the remains

and indeed the access track/path down the cliff has been disrupted by this slippage.

"Faced with a huge and expensive

logistical problem the council has to accept that it cannot afford to direct

limited funds needed for service provision to provide

protection to the pit remains from above and below. "In order to at least

retain a record of the present remains, an

archaeological survey study and report has been undertaken by Lancaster University

Archaeolo-gical Unit (for which support

was provided by English Heritage). "This document including sketches, drawings

and photographs, has been placed in the

Whitehaven Library and a copy has been retained by the Council. "The Council

has approached English Heritage and

DEFRA for assistance with funding for preservation and/or protection from the

sea. English Heritage were approached to

provide a valuation of the remains but eventually declined. "This may have

enabled assistance for a study and potentially

remedial works to the gabions, but at present the Council is unable to secure

assistance in this area. "Even if some protection

from the sea can be provided a strong risk continues that the slippage from

above will gradually affect the remains."

Backup copy on this server of background

research For National Trust by Cranstone Consultants 267 Kells Lane, Low

Fell, Gateshead ,Tyne and Wear NE9 5HU .

A booklet (available at the Haig Pit Museum) based on the evidence

of an 1841 Parliamentary inquiry into the terrible conditions

down the coal mines. Among the shocking details it lists are how

young the children were when they started work. One youngster,

John Daly, started work when he was only six years and nine months.On

average the children worked 10 to 12-hour days.Fourteen-year-old

James Rotherey, who worked in Lord Lonsdale's William Pit, told

the inspectors: "I go down at six and come away at seven,

or perhaps eight."When the Childrens' Employment Commission

travelled to West Cumbria in 1841, conditions were uncovered that

would shock even the most hardened aid-worker fighting to outlaw

child labour in foreign countries today.

The inspectors reported: "The morals of the children are

very indifferent. They are as ignorant as it is well possible

to conceive children to be; nor are the lads from 13 to 18 years

old one jot more informed. It is not to be supposed that children

confined for 12 hours in a coal pit can have opportunities for

any sort of education.'' John Greasley, the Haig Pit Restoration

Group's secretary, said: "The evidence was so offensive,

even to the Victorian public, that legislation was quickly introduced

to outlaw the employment of women and girls underground and boys

under the age of 10. The accounts vividly portray the hardships

these children endured at the hands of their masters.''One 11-year-old

told the inspectors: "I get up at four and have my breakfast

of porridge and milk and a great bit of bread. I have a bit of

bread and butter and cheese in the pit at 12 o'clock."I never

play but I'm not tired. I don't go to church or chapel, I have

never heard of Jesus Christ.''A 15-year-old states: "I had

6d a day as a trapper. It's hard work, we have to hold back the

baskets of coal going downhill."We have our left shoulder

against the horse's tail and our right leg right against the tram.

There is no brake to keep the trams back''The surgeon employed

by the mines told the inquiry: "I do not consider 12 hours

too much for either men or boys, considering the work they do.

The boys' accidents generally arise from the right leg slipping

off the frame of the tram as they are stopping them going down

hill.''Pit accidents claimed many of these youngsters. In 1837,

at one of Henry Curwen's pits, the owner's greed in pushing work

two miles out under the sea led to the sea breaking in. No one

was ever able to explain exactly what happened where the sea broke

in, as none of them escaped

The Coal Baron

Sir James Lowther was the land owning magnate who carved up much

of the new coal wealth of West Cumbria.

And in his enthusiasm to exploit the riches underground he was

not averse to some slick wheeler dealing.

In 1742 the Governors of St Bees public school leased all their

coal workings to Sir James Lowther for just £3.50 a year.

But this matter became the subject of a major court trial in 1821

when charity commissioners took action against Sir James. Their

action came about after someone cried Foul. Their study of the

matter uncovered the fact that the 1742 decision to lease at such

a low rent had been taken when both Sir James and his agent, John

Spedding were sitting as Governors. The court ruled that the lease

was nul and void.

The descendants of Coal Baron Lord

Lonsdale (the Lowthers) are still enjoying the wealth from their

Cumbrian landholdings.

According to North West Business Insider magazine in 2009 The Earl of Lonsdale's

Lakeland Investments, which owns some 72,000 acres of land, is estimated to

be worth £15 million. Meanwhile Lord Cavendish of Holker, who's family

were big in iron ore, are said to be worth £10 million.

Our own well known Lakeland

poet William Wordsworth saw his family financially crippled when Lowther

refused to pay a debt to the poet's deceased father John's estate. The legal

battle was dragged on for years by Lowther.

William Brownrigg was born on 13th of March 1711/12 at High

Close Hall in Cumberland, the first son of George & Mary Brownrigg.

He was baptised in Crosthwaite church a fortnight later. His mother

was the daughter of Henry Brownrigg of Armagh, Co.Wexford, and

cousin to George. Their status was that of minor gentry, and their

estate was at Ormathwaite Hall.

Having opted for a medical career, William took up a post in London

in the early 1730's, in a training role, before matriculating

to Leyden University under Hermann Boerhaave, before obtaining

his doctorate, and returning to Whitehaven in January 1737, to

join a partnership with Dr Richard Senhouse, who was himself a

Leyden graduate. This partnership was short-lived, however, as

Senhouse died in October of that year. Brownrigg consequently

took over the practice, and quickly attracted the attention of

Sir James Lowther, the major local landowner and his most influential

new client.

As a consequence of a serious firedamp explosion in Corporal Pit

on the 5th of August of that same year, Brownrigg was appalled

at the loss of life incurred (twenty-two men, a woman, and 3 horses),

and so he began an investigation of the natural gases that caused

it. Brownrigg had studied natural sciences as part of his degree

at Leyden, and combined his treating of the colliery workers with

that of what he believed were the causes of their ills.

Due to Lowther's patronage, Brownrigg became a contemporary of

John Spedding, the Agent of Lowther's estate, and of Carlisle

Spedding, John's brother, and Agent to the Collieries. As a result

of this closeness, he met and eventually married John's 20-year

old daughter, Mary in August of 1741.

In later years, Carlisle Spedding, who spent a great deal of time

underground amongst the men, trying to allay their fears of further

explosions, was himself badly affected by the poisonous gases

of the mines, and was treated by Brownrigg for their effects.

Spedding was eventually killed in another explosion underground.

Before his demise, Carlisle Spedding and William Brownrigg spent

considerable time together working to understand the gases and

how to make working life underground more healthy and bearable

to the men. Two innovations of Spedding's were the Flint Mill,

and the practice of "coursing" or directing ventilation

around the workings in order to remove still and poisonous air.

Sir James Lowther had, in the early 1730's, prior to Brownrigg's

arrival, spent some time in collecting firedamp in bladders, and

experimenting with them, before presenting experiments before

the Royal Society in 1733 and 1736. Carlisle Spedding had himself

written papers in support of these activities, one of which was

presented by Lowther in 1741, supported by an additional paper

by Brownrigg, which Lowther passed to Sir Hans Sloane, President

of the Society, and which, in April 1741 was placed before the

Society. Brownrigg followed this by three more over the following

thirteen months, on the relationship of these gases to epidemics,

mineral waters, and the nature of common air. As a result of these

papers, in May 1742, Brownrigg was elected a Fellow of the Royal

Society. His Patron, Sir James Lowther paid the twenty-two guineas

required to secure this honour as a life membership.

It was during this time, early in 1743, that Carlisle Spedding

backed Brownrigg in proposing to Sir James Lowther that a laboratory

should be built to facilitate his research. The plan was to build

a small "hut" near to one of the pits, to which Spedding

would convey fire-damp in a series of pipes. As well as the research

into the "damps", Brownrigg could also continue his

"chemical affairs", efforts that Lowther supported to

the extent of contributing £10, which was half of the building

costs of the laboratory.

Although Brownrigg had a large practice of local gentry (between

Maryport and Millom), he also treated many of the poor also. In

April 1743, Whitehaven was gripped by an epidemic, and Brownrigg

attended anyone in need, sometimes in the most appalling conditions,

such that he worked himself into near exhaustion, a condition

reported by John Spedding (his father-in-law) Chief Agent to Lowther's

estate, to his master in London, as so ill he was "like to

have died."

This experience in dealing with this outbreak, stood him in good

stead later, when in 1771, plague broke out in Europe, and he

published a paper through the Royal Society, advising on treatment

if it should arrive in England.

This epidemic and Brownrigg's subsequent illness, delayed the

building of the laboratory, but it was finished, complete with

installed leaden gas pipes, by July, and a lease was granted on

the 10th of September for a supply of gas from Peddlars Pit for

life, or as long as he remained in Whitehaven, at a peppercorn

rent.

Indeed, a search of Lowther's Rent Books, reveal that Dr Brownrigg

leased Roughfields, Croft and Acredale tenements in a part of

Daniel Gibson's Corkickle estate lease for £11 in 1743.

(This property contained a "Little House, Barn, and garden"

which were there in 1732, during the previous tenant, John Fisher's

lease. This is probably the house and garden shown on Mathias

Read's picture of 1736 near where New Houses were later to be

built) The rental fee dropped to £8 in 1744. Although the

remaining accounts for the 40's are not detailed, in 1751, the

description again included "Littlehouse and garden",

and the fact that the lease was to expire in Candlemas 1768. One

must assume that this was the case, for, in 1771, the lease had

passed to John Dixon. The only other mention is that Brownrigg

was in three years arrears by 1769 at £24, as was John Dixon

by 1772. Elsewhere in the accounts Daniel Wood is said to have

held a garden behind New Town.

It may be, that the £20 cost of creating a laboratory, was

in fact to convert or replace an existing building, possibly the

Littlehouse and Barn referred to above.

So, the experiments with mine gases continued, the gases being

fed to a series of furnaces in the laboratory, where their nature

was investigated. During this, Brownrigg noticed a marked increase

in the pressure of gas supply, which, he later realised, coincided

with a drop in barometric pressure. This finding was again the

subject of a paper to the Royal Society in December 1744. It was

this, that was probably his biggest breakthrough in predicting

the increased risk of explosions in the mines, as the increased

danger of concentrations of gas underground, could now be determined

by checking a barometer. This innovation has been used right up

to present day. Another such paper was presented in June 1749.

Brownrigg declined to allow his papers to be published, as he

intended them to be part of a work on a History of Coal Mines,

which he was still hoping to write in May 1754. Two years later

an outline of this work was read to the Society by Dr Stephen

Hales, but was never completed, although in 1765 his other works

on natural gases produced in spa waters was printed, following

his visit to Spa in Belgium. It was this latter work that was

deemed by the Society to be the best original paper of the year,

and Brownrigg was duly presented with the Society's Copley Medal

in 1766. A further paper on his chemical researches was presented

in 1774.

Also during this time, Brownrigg carried out experiments in distillation,

contributing a paper in 1755 contrary to Hales's methods of combining

air with water in a distillation vessel, which he thought might

be applied to the boilers of steam engines. As there were then

five such engines working at Whitehaven collieries, Brownrigg

consulted his colleague Carlisle Spedding on the possibility of

increasing efficiency in this manner. Although Spedding was killed

before Brownrigg could reply, he later advised Hales that they

considered that the air would pass into the cylinder and prevent

a good vacuum forming when the steam condensed. Brownrigg felt

that mechanical agitation might prove better, and also the use

of superheated steam. In this latter thought he was far in front

of the field, as it was to be towards the end of the nineteenth

century before the technical aspects were perfected.

Brownrigg was deeply interested in other, non-colliery aspects

of natural sciences, in 1748 having experimented with methods

of producing better common salt, and during 1741, in conjunction

with Charles Wood (his brother-in-law) carried out experiments

on smelting platinum ore, obtained by Wood whilst an assayist

in Jamaica, but originally smuggled from Cartagena in what is

now Colombia. This was believed to be the first introduction of

platinum into Europe, although the Spaniards were known to have

used it as augmentation of sword hilts, alloyed with gold. On

minerals too, Brownrigg contributed a paper in 1774, detailing

twenty specimens found in Whitehaven collieries, including green

vitriol, and Epsom salts, and earned the accolade of "the

bright star of natural history." All this, coupled with his

knowledge of botany, gained him a reputation such that his opinions

were sought by eminent scientists like Benjamin Franklin, with

whom he conducted experiments on Derwentwater in 1772, in support

of Franklin's hypothesis that stormy waters could be calmed by

pouring oil on them.

Brownrigg again became the hero of the working classes, when,

during outbreaks of Gaol Fever (Typhus) in 1757 and 1758, he proposed

that the poor should be treated at the public expense, prompting

his protégé Dr Joshua Dixon, a chemist and apothecary,

to found the Whitehaven Dispensary in 1783, in a building at 107,

Queen Street donated by James Hogarth, which was funded by public

subscription. Brownrigg, although no longer active in Whitehaven

by then, was a subscriber, and held a position as one of the Vice-Presidents.

The beginning of the end of Brownrigg's prominence in Whitehaven,

was in 1760, when his father died, and William inherited the Ormathwaite

estate. This took an increasing amount of his time, and diversification

into agriculture and estate management, distracted him somewhat.

The Whitehaven Census of 1762, did list him as renting a house

and garden at 24, Queen St, owned by Peggy, his sister-in-law

and another member of the Spedding Clan, then married to Anthony

Benn.

By 1770, probably following the termination of the lease of the

land his laboratory was on in 1769, Brownrigg moved from Whitehaven

to Ormathwaite, and built a new laboratory there. He entertained

various eminent guests like Franklin for some years, but appears

to have made some financial mistakes, which, coupled with a failing

mental capacity in later years, caused him to hand over financial

control in 1787 to his wife's nephew, John Benn, who, on William's

death in January 1800, inherited his estate.

The reader can probably detect from the content of the Brownrigg

account, that the author is interested in establishing the location

of the laboratory in which such significant work was carried out.

It was during a recent talk by Colin McCourt of the Beacon, author

of the new book on New Houses, that interest was sparked in the

building at the northern end of the Castle Row renovation works

by Groundwork.

This structure consists of a ground floor wall of very well cut

and dressed stone, containing a large Gothic-arched centre door;

two smaller ones each side, and two similarly-shaped windows outside

them. All these apertures are filled in with rough stone and mortar.

Long thought to have been a miner's hospital, the Dispensary,

a church, or a school, due to its fine stonework and windows,

it now appears to be none of these things.

Colin, in his book and talks, points out that the miner's hospital

was in Top Row. His own researches suggest that churches and schools

are excellent keepers of records, and yet no such records exist

for this building.

A search of old maps all show this wall as exactly that; a wall.

The earliest such depiction is dated 1792. It is perfectly flat,

straight and perpendicular, with oblong stones in a repeating

pattern. Who would build a "wall" with such perfectly

cut stone, with arched windows? Nobody.

A search of Pellin's earlier town plans reveal a roadway leading

up from Rosemary Lane in 1705, but nothing built on it. Mathias

Read's Prospect of Whitehaven in 1736 however, appears to show

a house and garden in that area.

Daniel Hay established, through a plan of the Howgill Colliery

dated 1791, that Pedlar Pit, the pit from which Brownrigg obtained

the gases for his experiments, was below and just along Castle

Row from this building. Newtown Pit was right beside the building

at the fork in the path up to Arrowthwaite. Remember, New Houses

were not begun until 1788. If it were a hospital, church or school,

who would it serve? Nobody lived up there.

To return to the talk; one of the slides shown, was of Middle/Castle

Row, and showed this building. Once enlarged, the photo, believed

to date from 1929, showed that there was then a higher wall, including

another Gothic-arched window on the first floor. Beneath this

window was a water-box and downspout, suggesting a use of water

on an upper floor. Careful examination of the photograph also

revealed the "ghost" of two other windows, one with

a lintel, that had probably collapsed and been filled-in as a

castellated wall. As the northern end of the wall is not shown

on the photo, it must be supposed that by looking at the positioning

of the three indicated windows, there would have been a fourth

on the first floor. So, definitely not a wall, but a fairly substantial

building.

Who could afford to build such a quality structure, and why?

The Lord of the Manor, Sir James Lowther; the Town and Harbour

Trustees, or a local merchant or gentleman. Why? Nearly all businesses

then relied on the Harbour; why build seventy feet above sea-level?

The other main businesses were agriculture and coal. It was certainly

not a farm building, as the land there then was either gardens

or unworkable. Coal then? Most pit structures then were of wood,

except the engine houses for beam engines, which were tall and

made of much rougher stone. So who could build it?

Dr William Brownrigg. He was a gentleman; he had the backing of

the Lord's Agent (his brother-in-law) and of Lowther himself,

and he is said to have had his laboratory next to Pedlar Pit.

Did I hear somebody say "So what?"

Well, we have a town founded on coal and shipping. We have a harbour

that has been transformed by people with vision, into a significant

earner for the local economy. We have a major funding package

designed to similarly transform the coastal strip and Pow Beck

corridor. We have a structure we suspect was used by one of the

leading research chemists and physicians of his time, in a sufficiently

preserved state that we can still rescue it. Finally, we have

a local authority that not only played a major part in the regeneration

activities above, but also owns the land and the building that

stands on it.

The aim is, to first form a group of volunteers, backed by local

authority expertise, who could clear the top of the building of

undergrowth, to establish that there are indeed walls beneath

it. Then, after structural and drawn surveys, the infill of waste

needs to be removed from the top first, before removing the infill

of the central door, and clearing the entire inner area. This

would be overseen by archaeologists, and all "finds"

would be carefully catalogued, and retained in Whitehaven. Whether

we can ever prove that it was indeed Brownrigg's laboratory, remains

to be seen, but do we really want to let the rest of it fall down?I

think not.

D K Banks, Researcher

West Cumbria Mines Research Group.

Gordon Nicholson has supplied fascinating pictures of the Brake

when it was operating before closure in 1986.

“The Corkickle Brake was constructed in 1881 by the Earl

of Lonsdale's Whitehaven Colliery Company to handle the output

from Croft Pit. There were sidings at the bottom of the incline

which joined the Furness Railway between Corkickle Station and

Mirehouse Junction. The Corkickle Brake was originally operated

by a steam winding engine at the Brake Top fed with steam from

three Cochrane Boilers. The incline initially mostly dealt with

coke traffic from the coke works at Ladysmith Colliery together

with by-products in tank wagons which went mainly to the steelworks

at Workington and Barrow. The 1930's brought hard times to West

Cumberland and when the coke works at Ladysmith closed in 1932

the Corkickle Brake was then left unused and the weeds and rust

soon began to flourish. The two partners Frank Schon and Fred

Marzillier who started the company Marchon Products Limited in

1939 moved to Whitehaven in 1940 and began manufacturing firelighters

in Hensingham. Not long after coming to Whitehaven the company

started to market chemicals as raw materials for detergents and

in 1943 moved to the site of the former Ladysmith Coke ovens at

Kells. By 1955 Marchon had 1,500 employees and was firmly established

as one of the major manufacturers of detergent chemicals.

For over twenty years the Corkickle Brake had laid idle but a

new period of activity was about to begin. By the mid 1950's the

Marchon railway traffic was increasing dramaticaly and it was

affecting the nearby collierys as it had to use the Howgill Brake

down to the Harbour. In 1953 the NCB handed over the long disused

Corkickle Brake to Marchon to modernise and work the line themselves.

The brake was ready for testing in Spring 1955 and with full traffic

begining again in May of that year and for the next 30 years the

Corkickle Brake was back in service.” But all that came to

an end in 1986 and the only reminder of its past is the local

place name of “Braketop”. Sheila Cartwright, can be

contacted on Tel. 019467 25713

In 2017:West Cumbria Mining hoped to start the extraction of coking coal off

the coast of St Bees, with a processing plant on the former Marchon site at

Kells. Coal would be treated at a processing plant using around a third of the

former Marchon site and covered by a dome, before being transferred to a train

loading facility on a siding built by WCM

south of the new Mirehouse train station.

Collieries of Whitehaven /England's

first Undersea mine/Haig

Mine Museum /Klondike in Cleator Moor /

Whitehaven's mining professor

Information on the mining history of Cleator

Moor